The History of Fleer and SkyBox

The O. Holstein business was established in 1849 by Otto Paul Holstein, a

spice and extract merchant in Prussia. The Holstein family arrived in

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in May 1885. On August 6, 1885, daughter Pauline

married Franz Heinrich Fleer, an immigrant from Westphalia.

Frank Fleer partnered with Otto Holstein and formed the Frank H. Fleer &

Co. Inc. as a confectionary company. In 1886, Frank and his younger brother

Robert found early success selling Guru-Kola Gum and Pepsin Gum as digestive

aids. Early advertising campaigns and labels featured a portrait photograph

of Frank.

In 1888, Otto Holstein travelled through Europe to procure supplies of

almonds, gelatins, and lemon oils. Inspired by Jordan almonds, Robert

experimented with adding a thin candy coating to pieces of chicle gum. The

name "little chiclets" was first used on October 1, 1899, and a patent was

registered on

February 23, 1904 . Fleer introduced the Chiclets brand in the spring of 1904 and the

crunchy peppermint combination was a nationwide hit. The factory on Hamilton

Street was expanded after the first 60 days of sales.

In 1906, Fleer developed an unsuccessful bubble gum called Blibber-Blubber.

The product was abandoned due to the concoction being too sticky. The

bubbles splattered and sometimes required a solvent to remove.

Chiclets sales continued to rise. In 1908, an additional Fleer factory was

constructed in Toronto. On June 19, 1909, Frank Fleer and four other gum

manufacturers formed a $6.7 million trust called Sen-Sen Chiclet Company.

In December 1913, Fleer left the Sen-Sen board and established the Frank H.

Fleer Corporation with $150,000 in capital. In 1914, Sen-Sen Chiclet Company

and the Chiclets brand were absorbed by the American Chicle Company. Frank

H. Fleer died of a stroke on October 31, 1921. Fleer business operations

were led by son-in-law Gilbert Mustin.

Cigarette insert cards were introduced in April 1877 by New York

manufacturer Thomas H. Hall. Baseball cards were first sold with chewing gum

in 1888 by G&B Gum in New York and H.D. Smith & Co. in Cincinnati.

In 1923, Fleer advertised a set of 120 "famous person" strip cards. One card

was included with every five-cent pack of peppermint flavor Bobs and Fruit

Hearts chewing gum. The heart-shaped gums were similar to Chiclets.

The 1923 Fleer cards are listed as E241 in The American Card Catalog.

The set is comprised of five different strip card series including the W515

baseball set. Each card panel is printed with a Frank H. Fleer advertisement

on the back. A complete set of 120 Fleer cards has not been documented.

Based on observations of uncut sheets, it is estimated that only 110

different Fleer cards were actually distributed. Several cards feature

illustrations based on photographs copyrighted by Underwood & Underwood.

In August 1928, Fleer accountant Walter E. Diemer successfully refined a

bubble gum formula using latex and pink food coloring. Pink was the only

abundant color available and Diemer did not patent the recipe. According to

Diemer, ''I was doing something else and ended up with something with

bubbles.'' Pink remains a common color used for bubble gum products to this

day.

Market testing for the new invention began on December 26, 1928. Diemer

personally taught shopkeepers and salesmen how to blow bubbles. The International Gum Corp. of Massachusetts registered a patent for "Sure Pop Bubble Gum" in August 1929. "Dubble

Bubble Gum" debuted in early 1930 and sales for the one-cent chew exceeded $1.5

million in the first year. A series of six comic strip wrappers featuring

"Dub and Bub –The Dubble Bubble Twins" were copyrighted on September 20,

1930.

The first bubble gum trading cards began appearing soon after the

introduction of Dubble Bubble. One of the earliest known releases is the

baseball and film star series from Marble Bubble Gum Novelties of

Philadelphia (W553). In 1930, Fleer released a series of 16 die-cut discs as

premium prizes with

Whiz Bang

gum. The "Taka-Flyer" disc set features film actors and three Hall of Fame

baseball players: Goose Goslin, Lefty Grove, and Gabby Hartnett.

In 1935, Fleer released Cops and Robbers Gum (R35), a 35-card set

that included a stick of Dubble Bubble with each pack. The cards feature

perforated "Evidence" tabs that could be exchanged for a premium detective

badge.

By 1937, Blony bubble gum from Warren Bowman's Gum, Inc. dominated the market. Bowman claimed more than 60% of penny gum sales in America, a figure disputed by Fleer sales manager William B. Hunt.

By 1937, Blony bubble gum from Warren Bowman's Gum, Inc. dominated the market. Bowman claimed more than 60% of penny gum sales in America, a figure disputed by Fleer sales manager William B. Hunt.

During World War II,

latex and chicle supplies were diverted to the defense effort, sugar was

being rationed to households, and paper scrap drives were held to salvage

pulp. American Chicle, Beech-Nut, Leaf, Walla Walla, and Wrigley were

contracted by the government to supply gum for military rations. After

D-Day, gum from American and Canadian soldiers became widely popular

throughout the

Netherlands.

The Japanese occupation of the Malay peninsula cut off the crucial supply of

jelutong latex. Fleer was forced to temporarily suspend production of Dubble

Bubble from April 1943 until 1950. Limited shipments were sent to dentists

and drug stores. Legends of street prices reaching $1 per piece have been

reported.

In 1946, Fleer purchased a larger factory from the War Assets

Corporation located on North 10th Street in Olney, Philadelphia. Gilbert Mustin passed away on October 30, 1948. Ownership of the Frank H. Fleer Corp. was transferred to Norman P. Hutson, an engineer from Brooklyn. In a 1952 interview, Hutson stated that bubble gum was invented by Wm. J. Wischmann in Brooklyn and sold under the name "4X."

A new comic strip character named Pud was introduced in 1950. In 1968,

Dubble Bubble printed the one-thousandth comic wrapper.

-

Bazooka bubble gum was introduced by Topps Chewing Gum in July 1947.

Bowman Gum, Leaf,

Topps, and Swell released baseball card sets in 1948. An aggressive

competition arose over the image rights for professional athletes. In 1956,

Topps acquired the Bowman brand and player contracts for $200,000.

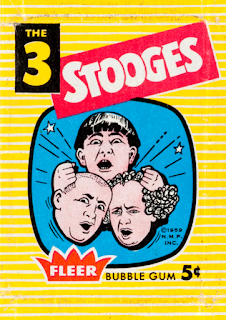

In 1959, Fleer released an 80-card series showcasing Ted Williams. The

exclusive deal removed the popular slugger from Topps sets. Fleer followed

with an

Indian series and a 96-card set for The Three Stooges. In

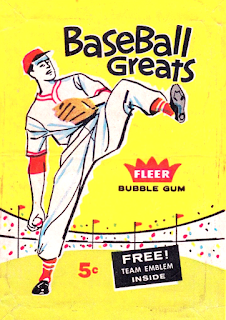

1960, Fleer released cards for the American Football League and a throwback

series of retired Baseball Greats.

Topps held exclusive rights to the National Football League and about 400

Major League Baseball players. In order to compete, Fleer offered athletes

$125 for a non-exclusive contract. In June 1961, Newsweek reported

the bubble gum business was worth an estimated $30 million per year and

Topps sales accounted for nearly half.

By 1964, Topps had signed nearly every active baseball player with around

6,500 exclusive contracts. In 1966, Topps forced the

Exhibit Supply Co. (ESCO)

to stop printing contracted players. In April 1975, Fleer filed antitrust

charges after being refused a license for baseball stickers.

On June 30, 1980, the Federal Trade Commission ruled that Topps had unfairly

restrained trade in the baseball card market. The U.S. Court of Appeals

overturned the decision in August 1981.

The Topps contracts contained exclusive rights to baseball cards sold with

gum or candy, so Fleer simply packaged cards with team logo stickers.

Donruss released a 1981 series that included a cardboard puzzle of Babe

Ruth.

Topps filed unsuccessful lawsuits against Fleer in 1982 and 1986 before

capitulating. The end of the two-decade baseball card monopoly allowed new

companies like Score and Upper Deck to enter the market. Topps stopped

including sticks of gum with baseball cards after 1991.

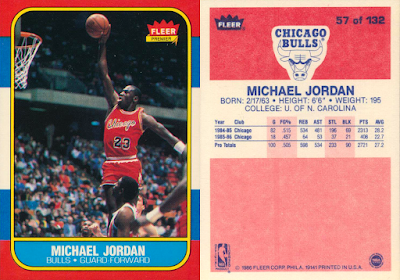

Fleer included a stick of Dubble Bubble inside each pack of basketball cards

from 1986–1989. Initially a sales flop, the 1986–87

Fleer NBA Basketball series is now sought after for containing the

Michael Jordan rookie card and other hall of fame inductees.

In 1989, Gilbert Mustin Jr. sold the Fleer Corporation to Charterhouse

Equity Partners for $75 million. The Charterhouse deal was led by former

Donruss executive Paul Mullan.

Impel Marketing Inc. was formed as a subsidiary of Brooke Group Ltd. on June

21, 1990. In October 1990, Impel released

Marvel Universe Trading Cards, a popular series featuring hologram

chase inserts. Similar sets followed for Walt Disney and

DC Comics

characters. Impel licensed various non-sport properties including

A Nightmare on Elm Street, G.I. Joe, Star Trek, and

Terminator 2: Judgement Day. The first sports release from Impel was

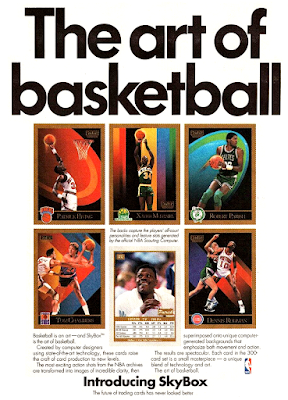

the 1990–91 Inaugural Edition of SkyBox NBA Basketball Cards.

Impel CEO Frank O'Connell was the former president of Reebok and former CEO of

HBO Video. In an interview with Wizard magazine, O'Connell explained

that the name Impel was not relevant to sports or entertainment. Testing

favored "skybox" as a recognizable term for the best seats in an arena. On

April 15, 1992, Impel Marketing rebranded as SkyBox International Inc.

Basketball legend Earvin "Magic" Johnson was signed as the first celebrity

spokesperson.

On July 24, 1992, Marvel Entertainment Group purchased Fleer from Charterhouse

for $265 million. In 1994, Fleer reported $38 million in gum sales and $245

million from trading cards. The combined sales from all retail trading card

companies in 1994 was more than $2 billion. Investor speculation and hype led

to larger print runs of cards, comic books, and

POGs.

On March 9, 1995, Marvel purchased SkyBox for $150 million. The card companies

were merged to form Fleer/SkyBox International, now holding major licenses

with the NBA, NFL, NHL, MLB, and NASCAR. Card sales began to drastically

decline following the MLB strike of 1994–1995 and the NBA lockout of 1995–1996.

On December 27, 1996, Marvel filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection.

The Dubble Bubble plant in Olney, Philadelphia, was used to cut and collate

Fleer cards. Vice President of the Hobby Division Ted Taylor reported that, "a

lot of cards walked out the doors in lunch pails, briefcases and other such

carriers." Collectors commonly refer to stolen factory cards as

"backdoored." Entire cases had been taken from the plant through

inside sources. Although Fleer did not distribute to hobby dealers, complete

sets would appear in local card shops before the official release dates.

Production at the Dubble Bubble plant stopped on November 26, 1995.

Employees arrived after Thanksgiving weekend to find the gate locked. The

Onley factory was officially shut down on January 26, 1996. The closure was

featured in the April 9, 1996, broadcast of ABC News Nightline.

According to Fleer/SkyBox CEO Jeff Kaplan, "It was largely confectionary

driven and had little to do with the baseball strike." Dubble Bubble

production continued at a Fleer factory in Byhalia, Mississippi.

In 1998, the Dubble Bubble brand was purchased for $13 million by Concord

Confections in Canada. Concord was acquired by Tootsie Roll Industries in

August 2004 and the Dubble Bubble recipe was changed. Tootsie Roll introduced

the "Original 1928 Flavor" in 2015. The new Dubble Bubble wrappers featured 60 classic

Pud comic strips.

By 1999, the entire trading card industry had crashed. Marvel sold

Fleer/Skybox for $26 million to Rite Aid founder Alex Grass. The SkyBox

branding stopped appearing after 2000. The Upper Deck Company made an offer of

$25 million in 2003, but the Grass family declined. In 2005, Fleer/SkyBox

filed for bankruptcy with debt nearing $40 million. On July 15, 2005, the

Fleer/Skybox brand was auctioned to Upper Deck for only $6.1 million. The last

set issued by Fleer in 2005 was American Idol Season 4, featuring

Carrie Underwood.

On September 9, 2005, Fleer/SkyBox held a bankruptcy auction at the Radisson

Hotel in Mt. Laurel, New Jersey. Millions of cards and other memorabilia from

the Fleer and SkyBox archives were sold to the public. The massive sale

included autographs, errors, test proofs, uncut sheets, and unstamped

parallels.

A PDF catalog of items listed by the Continental Auction Group, Inc. can be

viewed here.

Since the auction, multiple examples of aftermarket serial number alterations

and counterfeits of rare sports cards have been identified. Collectors are

advised to conduct proper research on products produced by Fleer and SkyBox

from 1986–2005. Hobby experts at the

Blowout Cards Forums

have experience detecting trimmed cards and forgeries.

Chiclets are currently produced by Mondelez International, formerly Kraft

Foods. Dubble Bubble from Tootsie Roll is commonly seen in Major League

Baseball dugouts. The Marvel trading card license was acquired by Fanatics,

Inc. and the Topps brand in 2024.

The last baseball card series containing the Fleer branding was issued by

Upper Deck Entertainment in 2007. Fleer and SkyBox basketball releases

temporarily stopped after 2008–09. The Fleer name returned in 2011, followed

by SkyBox in 2015. On June 13, 2024, Upper Deck announced a partnership with

Warner Bros. Discovery Global Consumer Products. The Fleer and Skybox brands

will feature

DC Comics characters beginning in 2025.

-

"Advertising vs. Trust Methods." Printers' Ink, vol. 56, no. 3, 18 July

1906. pp. 18–22.

"A Chewing-Gum Campaign." Printers' Ink, vol. 47, no. 11, 15 June 1904.

p. 6.

Allen, Frank Hales.

"Penny Sales Pay Dollar Dividends."

Nation's Business, vol. 26, no. 8, August 1938, pp. 33–36, 68–69.

"Bubble Gum Fight Enters Round 2; Topps Defends Its Rights in Baseball-Card

Market."

The New York Times, 18 February 1964, p. 71.

"Bubble Trouble."

Newsweek, vol. 57, no. 26, 26 June 1961, pp. 73–74.

"Chewing Gum."

Nation's Business, vol. 26, no. 12, December 1938, p. 52.

Cook, Bonnie L. "Frank H. Mustin, 94, former Fleer bubble-gum company executive." The Philadelphia Inquirer, 14 March 2018.

Goodnough, Abby.

"W.E. Diemer, Bubble Gum Inventor, Dies at 93."

The New York Times, 12 January 1998, p. B7.

Hylton, J. Gordon.

"Baseball Cards and the Birth of the Right of Publicity: The Curious Case

of Haelen Laboratories v. Topps Chewing Gum."

Marquette Sports Law Review, vol. 12, no. 1, Rev. 273, 2001.

"Impel Marketing Inc."

Forbes, 15 October 1990, p. 156.

Isaacson, Kevin.

"Pinnacle praised, Topps and Fleer/SkyBox knocked, on 'Nightline'."

Comic Buyer's Guide, no. 1173, 10 May 1996, p. 6.

"Liggett to Change Its Focus With Shift From Cigarettes."

The New York Times, 20 June 1990. p. D1.

"Marvel to buy Fleer for $265 million."

United Press International, 24 July 1992.

"Marvel to buy rival trading-card maker."

New York Times, 10 March 1995. p. D3.

"New Corporations."

Oil, Paint and Drug Reporter, vol. 84, no. 27, 29 December 1913, p.

63.

Frank H. Fleer & Co.

"Chiclets."

US Patent 42,113. 1 Feb 1904.

"O. Holstein, Importers of Mexican Vanilla Beans."

Oil, Paint and Drug Reporter, vol. 36, no. 8, 21 August 1889, p. 46.

Shamus, Gareb.

"A Talk With President Frank O'Connell."

Wizard, no. 11, July 1992, pp. 18–21.

Swaab, Jr., Mayer M. "That Fleer Face." Printers' Ink, vol. 21, no.

11, 15 December 1897, p. 8.

Taylor, Ted.

"Fleer/SkyBox Sale Finally Goes Through."

Philadelphia Daily News, 4 February 1999.

Taylor, Ted.

"Time To Turn Out The Lights At Old Fleer Factory."

Philadelphia Daily News, 25 January 1996.

Timoner, Vic.

"Popping of Dubble Bubble Sweet Music to His Ears."

The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 28 December 1952, p. 8.

"Trade Items." Oil, Paint and Drug Reporter, vol. 36, no. 12, 19

September 1888, p. 7.

United States District Court for the Southern District of New York.

Topps Chewing Gum, Inc. v. Major League Baseball Players Association, 641 F. Supp. 1179 (1986), 1 August 1986.

"Walter Diemer, Inventor of Bubble Gum in 1920s."

Chicago Tribune, 13 January 1998.

Woolley, Wayne.

"Fleer Closes Plant In City That Pioneered Bubble Gum."

Press-Republican, 4 December 1995, p. 7.

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

%20p%20541.png)